VIA FRANCIGENA - EMBRUN TO PAVIA - SEPTEMBER 2023

This is a picaresque and mostly true account of the sixth stage of a pilgrimage from Canterbury to Rome, which follows a meandering version of the ancient pilgrimage route called the Via Francigena. I started the trek in 2015 with my son, Mike, and hiked for roughly three weeks each successive year until interrupted by the Covid lockdown.

The current stage resumes where I left off in 2019 – in the village of Embrun in the French Alps. It covers some 350 km and crosses the Alps

into Italy through the pass at Montgenevre, ending in the town of Pavia. It will take two more stages to reach Rome,

which lies about 750 km south of Pavia.

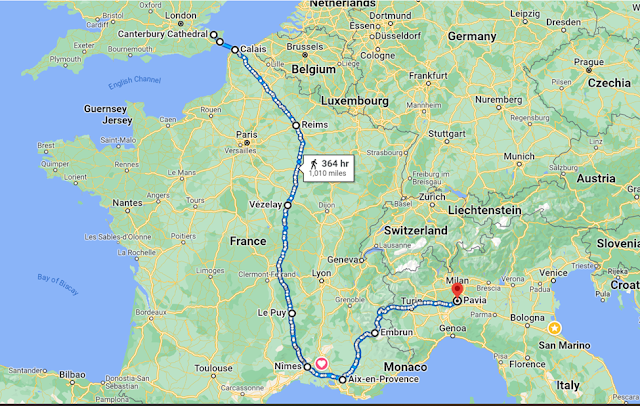

Here is a rough map of the entire route so far. It doesn’t correspond to the actual hiking path but at least shows the start and end points for each year of the hike:

(2015) Canterbury to Reims via Dover & Calais

(2016) Reims to Vézelay

(2017) Vézelay to Le Puy

(2018) Le Puy to Aix-en-Provence via Nimes & Arles

(2019) Arles to Embrun

(2023) Embrun to Pavia via Turin

Day 1 – Thursday, 7 September: Embrun to Chateauroux-Les-Alpes – 8.5 km

There are three basic rules when backpacking. The

first and most important is never to leave anything behind. Hardly less

important is the second rule – bring lots of water with you. And finally,

when you stop to rest along the path, always look carefully before you sit

down.

I had these rules in mind as I trudged with my pack through

the deserted streets of the village of Embrun, having slipped out of my B&B

by the cathedral at 7.30 am. My plan was to have breakfast at the Hotel

de Mairie in the main square – the only place open at this hour – and then head

off on my hike. Although the temperature was a chilly 13 degrees, the

predicted high would be a scorching 30, so I wanted to get started as early as

possible. My destination for the day was the village of Chateauroux-les-Alpes,

only 8.5 km distant but across a range of mountains that circled Embrun to the

north.

The breakfast room at the hotel was packed with middle-aged

French men, all wearing rugby shirts evidently bought when they were a bit

younger and slimmer. The explanation, as I learned later, was that the

World Cup of Rugby would be starting on Friday, with the host country (and

favourite to win) being France itself. So I was definitely the odd man

out as they eyed me curiously in my hiking gear. At the end of

breakfast, I stood up, checked the straps on my pack, studied the table to make

sure I hadn’t left anything behind (Rule #1), set my wide-brimmed hat at a

rakish angle, and left the room. Moments later I was pursued by one of

the rugby lovers. “Monsieur,” he called brandishing my hiking poles, “You

left these behind!”

So much for Rule #1.

But anyone could make a mistake like that, I told myself as

I embarked on a search for a second bottle of water to supplement the one I was

already carrying (Rule #2). I finally found a small bakery that stocked

such a bottle, and paid for it in cash.

This involved opening the pouch slung around my neck, extracting a

sandwich bag, and fishing inside for a 10 euro note, much to the suppressed

amusement of the young woman behind the counter. I carefully took my

change, placed it in the correct pocket of the pouch, rolled up the sandwich

bag and tucked it away, and with a friendly “Au revoir” set off for the

door. “But monsieur,” the lady called, “Your water. You left

it behind!”

Yikes! A near-violation of both Rules #1 and 2.

Ah well, it’s an early-morning thing, I muttered, as I

started up the steep road out of the village, whose posts were marked with the

characteristic red and white symbol of a French GR (Grande Route) hiking

trail. Two hours later, and 500 metres higher, I stopped by the side of

the farm-road for a rest. I took great care to find a rock in the shade,

used my hiking poles to clear away some spiky plants, and sat down to remove my

boots, giving my feet the chance to get some fresh air. I knew better

than to place my feet on the ground, because my socks would pick up all sorts

of bits and pieces, but rested them on my boots. Yet when I started to

re-boot myself a bit later, one of my feet slipped and landed in the layer of

dirt at the edge of the road. And not just dirt – as I soon

discovered. An ancient layer of dried manure.

Rule #3 bit the dust, or something worse.

What more is there to tell you about my first day on the

road? Well, the initial part of the hike was all up-hill, nearly three

hours of it. And the gradient varied from merely steepish, to very steep,

then crazy steep, then a-cliff-in-everything-but-name. Yet the

countryside was extraordinarily beautiful – with views across the valley of the

Durance River to the rugged mountains on the other side. A hiker’s

paradise.

The sound of water accompanied me much of the way, as brooks bubbled and gushed through channels at the side of the path, or spilled across the way. Though the day grew quickly hotter, with brilliant beams of sunlight flickering like strobe-lights through the branches as I moved along, there was plenty of shade on the path, except for the final descent into the village of Chateauroux-les-Alpes, where I found my B&B in a wonderful rambling Alpine-style house – located nearly at the bottom of the valley.

As I gazed northward toward the

mountain range where I’ll be heading tomorrow, I wondered if I’d have to climb another

500 metres to get out of the valley. Only time will tell.

Day 2 – Friday, 8 September: Chateauroux-les-Alpes to Eygliers – 18.5 km

There are a couple of backpacking rules I forgot about

yesterday, but which are worth mentioning here.

The first is to have a hearty breakfast.

And the second is not to fall off any cliffs.

Breakfast is pretty fundamental if you plan to walk in the

mountains for an entire day under the hot sun.

So why did I leave my B&B this morning with only a single croissant

and the rump end of a baguette in my stomach?

It doesn’t make much sense – particularly since the young landlord was a

trained chef and had set out a nice spread for me – his only guest for the

night. The explanation is that I’d eaten

a tremendous amount of food the night before – he’d served up an assortment of

local specialities: various meats and sausages, cheeses, salad items,

preserves. And I’d somehow managed to devour

the entire lot, while downing most of a bottle of a local red. So I was contrite – deeply so – and anxious

to set off into the wilds to atone for my sins.

Which only goes to show that an Irish-Catholic upbringing is no

preparation for life on the road.

So, to reprise the question I posed yesterday, did I have to climb 500 metres to get out of the valley? Not really, though there was a stiff ascent at the start which took me up to the village of St-Marcellin, perched on a rocky summit overlooking Chateauroux. But once there, I was launched onto a hiking trail that threaded its way along the side of a steep mountain slope, some 150 metres above the Durance River, with astonishing views up and down the valley. The path was tiny and often only inches from a ragged and eroded edge, where a stumble could become a tumble to eternity – or at best to the local emergency department.

But the sun was shining and the air was still cool, so I walked with a lighthearted step along the path, watching the weird folds in the mountains across the valley shift as the light changed. The exposed rock faces have layers and layers of strata, curving and writhing, giving one the sense of enormous stretches of time. Which was somehow appropriate, since the hike for the day was going to be pretty lengthy – some 22 km, more than double the distance covered yesterday.

Eventually the path left the Durance valley and took a sharp

turn to the left, plunging into a deep side-gorge. This wasn’t so much fun. The route takes you three kilometres all the

way along one side of the gorge, across a little wooden bridge, and than

another three kilometres all the way back the other side of the gorge – leaving

you hardly any closer to your destination, and proving once again that GR

hiking routes represent the longest possible distance between any two points.

By the time I emerged from the gorge, my stomach was telling

me what an idiot I was not to have stocked up more at breakfast. But luck was with me! When I finally limped down the trail to the

valley floor once again, I discovered a small restaurant-bar by the side of the

highway in the ancient village of St-Clement-en-Durance. It had a pleasant outdoor terrace where they

served me the dish of the day – a ham omelette with ratatouille and a green

salad on the side. Never in the history of humanity has a restoration of energy

and spirits been so rapid and complete.

Better still, when I showed the proprietor my hiking map, which directed

me to climb back into the hills along a hot tarmac road that looped crazily upward,

he laughed and said there wasn’t any need to do that. As a runner, he knew of a small service road beside

the railway track that led directly to my destination in the village of

Eygliers – a mere three to four kilometres alongside the river, as opposed to double

that distance, wandering like a drunken monkey through the hills.

So the railway service track it was, and here I am now at my

small auberge in Eygliers, sitting in the bar with a local blond (a blond beer,

that is) and feeling pretty good. Dinner

will be served soon in the dining room at the side, and the air is cooling off

as the sun sets behind the mountains.

On that happy note, I bring this blog to a close …

“But wait!” you say.

“What about the fall off the cliff?

Didn’t you promise us that?”

“I did nothing of the sort,” I reply. “I only told you about the rule against

falling off cliffs.”

“But why tell us the rule if it has nothing to do with the story?”

“Because there were many points at which someone might

have fallen off a cliff. But not

me! Did you really think I’m so silly as

to fall off a cliff?”

No need to reply.

Day 3 – Saturday, 9 September: Eygliers to L’Argentiere-la-Bessée – 21.5 km

I should have known something was up the moment I saw the

dog. A great shaggy white beast, standing as high as my hip, with a

strange bothered look about his eyes. He came around the bend in the road

ahead – an asphalted minor route winding up the side of the mountain – and he

veered vaguely toward me as I panted up the steep incline, hugging the

cliff-side to avoid the occasional vehicles that hurtled unexpectedly around

the curves. I kept a close eye on the dog, which seemed troubled by the

oppressive heat, and pushed onward, my hiking poles ready for combat.

Unleashed dogs in France are not the hiker’s friend.

Still eyeing me rather oddly, the dog continued past.

As I turned around to make sure he was actually gone, I saw him stop, as if

deciding whether ripping me from limb to limb was worth the trouble and the

mess. Then two men with small backpacks appeared from around the bend,

talking to each other – not unfriendly, but not paying me much attention

either, even when I called “bonjour!” They seemed to be the owners of the

dog. Problem solved.

But not so. A few more steps, and several sheep

trotted around the bend. I moved closer to the cliff to let them

pass. But then more sheep emerged, then even more, then more and more and

more – an enormous herd of sheep, at least two hundred strong, filling the

entire road. It became obvious that pressing to the side of the cliff was

not going to save me as the tide swept disconsolately toward me, their bodies

packed tightly together, jostling and bleating.

So I beat a hasty retreat and scampered (as best one can

scamper with a twenty pound pack) across the front of the mob to the safety of

the grass verge on the other side of the road, where the cliff dropped into the

valley. At the very back of the herd was a second dog, much like the

first, only black in colour, pacing back and forth, keeping the sheep in

order. The white dog had been the leader, scouting for obstacles.

No wonder he’d looked bothered.

And as I watched them disappear around the next bend I

wondered what happened when vehicles came speeding down and encountered them

blocking the road. In fact just minutes later, two cyclists in full

racing gear came tearing past. If I’d had my wits about me, I would have

shouted “Attention aux moutons!” But no doubt they’d have thought me a

half-wit.

Such is a hiker’s life in the mountains. And you may have noticed, dear reader, the reference to a steep road. Today was meant to have been a 20 km stroll by the Durance River, shaded by leafy trees, ducks bobbing in the eddies, the path as flat as a prairie pancake. That, at least, was what I’d figured from my small-scale map, photocopied from the GR hiker’s guide. How could I have been so naïve? The day featured not one but two separate steep ascents, the first at the start, perhaps 200 metres up into the hills on the east side of the river, the second in the early afternoon, to the west of the river, a good 400 or 500 metres up the side of the mountain, with the sun at its height and very little shade.

Once I got to the top, of course, the views were

magnificent, and I was rewarded by a lovely shady café in the tiny alpine

village of Poulons, where I downed a coffee and a half-litre of sparkling

Perrier with ice! Refreshed and reinvigorated, I renewed my march, down a

long winding road back into the valley.

Yes, in GR world, no sooner does one arrive at the top than one goes

down again.

Three or four kilometers along a nice flat stretch brought

me to my B&B in L’Argentiere-la-Bessée, a long shower, and an animated

dinner with three French couples of varying ages, also guests at the place,

along with my host, an outgoing lady with spiky blond hair.

My spoken French is improving in leaps and bounds, but my

comprehension lags behind. And so I struggled to follow the free-flowing

conversation around the table. The funniest moment came when, in the

midst of an exchange I couldn’t quite grasp, the man beside me turned and asked

if there was much cannibalism in Canada. “Cannibalisme?” I

inquired, somewhat taken aback. The whole table burst into

laughter. Turns out he was asking me about cannabis usage.

But misunderstanding is the spice of travel, as I’d learned

the previous night in the bar at my small hotel in Eygliers, which was filled

with a mix of tipsy locals and tipsy hikers, along with singularly harassed

landlady and her meagre staff.

It all started after I came down from my room for a drink

before dinner. As I sat there writing my blog, I noticed a group of

tallish, big-boned Brits, men and women of a certain age, who stumbled into the

bar in hiking gear, clearly exhausted and ready for a drink. After

talking to the landlady, they gave their orders and found a place on the

terrace outside. Some time later, I asked

the landlady if I could carry my unfinished beer into the dining area, or

perhaps pay for the drinks and the prix fixe dinner in advance. The

landlady, quite harried, gave me one glance and rather curtly quoted a price of

58 euros. I thought this was rather steep but figured the meal must be something

special. So I paid with my card and went outside on the terrace to

wait.

Nothing happened for quite a while – no menu, no waiter, no

food. But I wasn’t in any rush and continued sipping my beer and writing

the blog. Then I noticed a commotion at the English table, with various

individuals popping up and running back and forth from the bar. Something

to do with paying the bill. Eventually the landlady came out with one of

the Brits and, looking around, pointed me out and asked him if I belonged to

their group. He shook his head.

And it dawned on me that the 58 euros I’d paid was actually their

bill!

Hilarity on the part of the Brits and consternation on the

part of the landlady. But as I stood at the cash while she sorted things

out, I received my reward. One of the Englishmen (who’d observed me

talking to the landlady in my best French) asked me if I lived in Eygliers.

“No, no!”, I said, “I’m a Canadian, just hiking through.”

“Where to?” he asked.

“Into Italy,” I said.

He stared at me, eyes widening. “You’re going across

the mountains?”

“Through the pass at Montgenevre,” I said with my best

attempt at a Gallic shrug.

I was in a great mood the rest of the night, even though dinner was late.

Day 4 – Sunday, 10 September: L’Argentiere-la-Bessée to Briancon – 23 km

“Don’t take the route that goes along the river,” my

landlady urged me over breakfast, shaking her head. “It’ll be so

boring! Take the GR route that climbs into the mountains. The views

are just spectacular!”

She was right of course. It would have been awfully

boring to crawl along like a worm beside the river. But she was also

wrong. We all need a bit of boring in our lives.

Well, I thought to myself as I stepped out the door, I don’t

have to decide until I reach the place where the route forks – which was in the

village of L’Argentiere proper, a couple of kilometres away. Then I’ll stop

and take a look at the GR mountain path for myself and see how my legs feel.

Smart, eh? Just use your own eyes! Listen to

your body! What could possible go wrong?

As it turned out, plenty. For what I’d failed to do

was consult the detailed itinerary I’d drawn up earlier, where I’d painstakingly

calculated the length and elevation of the GR mountain route and come to the

conclusion it was not for me. Nor for anyone with a grain of sense. Sheer insanity.

So when I reached the point in l’Argentiere where the GR

route took a sharp turn to the left and climbed into an inviting pine forest,

the enthusiasm kindled by the fresh mountain air and brilliant morning sunshine

got the better of me. Forget the river, I said. It’s the mountain

route for me.

And how lovely it was for the first couple of hours, as I

climbed through a tiny village that clung to the lower slopes, admiring the

views that unfolded back into L’Argentiere and the vast mountain valley around

it. And how delightful it was to feel my legs responding to the

challenge, as I bounded along. I’m really getting back into the groove, I

thought. Just a couple of days into the trek and I’m almost in peak

condition.

Oh, the vanity of man! Oh, the sin of pride! Oh,

the cupidity of uninformed enthusiasm!

It was already mid-afternoon when I finally got to the route’s highest point at 1165 metres, some 700 metres above my starting point in the valley below, and some 50,000 calories expended getting there, or so it felt. I was totally exhausted as I dragged myself into the village of Bouchier, which thankfully boasted a café, where lean rock-climbers lounged about in the sunshine on the terrace. I was reminded of the fact that this area is a climbing mecca, with a multitude of well-known ascents, identified by name and signboard as I’d moved along the base of the cliff toward the village.

The frosty Perrier and strong coffee dispensed by the café perked up my spirits a bit. But I still had most of the hike ahead of me – some 11 kilometres to my destination in Briancon. And, as it transpired, the first section involved a slow tortuous descent to the valley floor. So when I staggered into the little town of Prelles beside the flowing waters of the Durance, it was already 6:30 pm – with 8 kilometres to go, and no gas left in the Slattery tank. But God, in his infinite wisdom, had placed a food truck at the entry to the town. Oh glory! A food truck selling pizza.

Two hours later I flew into Briancon on wings of pepperoni

and Emmenthal cheese, after an evening passing through fields above the Durance

river. Still starving, I found an

Italian restaurant open in the darkened lower town where I devoured an Insalata

Capricciosa, washed down by a huge mug of beer. In a state of zombified inebriation,

I marched up the long steep route to my Airbnb apartment in the ancient upper

town, where I fumbled in the darkness for the keys hidden on the balcony, and

finally made my entry at 10.30 pm.

Curtains. Zzzzzz.

Days 5-6. Monday-Tuesday, 11-12

September: Briancon to Montgenevre – 9

km

Trust the French to figure out how to make the world’s best cheeseburger. A deliciously crusty bun with a soft, almost flaky interior, the whole crammed with a hearty beef patty, topped with a slice of genuine non-plastic cheese, small tasty tomatoes, a pickle or two, and some kind of unidentifiable but flavourful sauce.

This is what I ate for breakfast at the boulangerie which,

after a long search, I’d finally discovered at the top of the steep old town of

Briancon, in preparation for a march up the Alpine pass that almost defeated

Hannibal.

Remember backpacking rule number – uh – whatever it is. Anyway it goes like this: Always have a hearty breakfast. But in France, dear reader, the gastronomic

capital of the world, this is not an easy task.

Believe me, I’ve tried.

Everything from croissants, to brioches, to tranches of baguette

slathered with butter and jam, to quiches filled with imaginative combinations

of exotic legumes. Nothing really does

it.

But in the boulangerie this morning I cast an eye on the

display of three different kinds of burgers.

They looked good. They looked

hearty. They looked like they could last

me the day. So I ordered the meatiest

one, along with a nourishing café au lait.

And it was everything it promised to be.

All my to-ing and fro-ing to secure a breakfast took up a

lot of time. So I was a bit late in

departing from my Airbnb apartment in a set of freshly laundered clothes,

courtesy of the washing machine crammed into the bathroom next to the toilet.

But no worries, I thought, today is not a long day. Yes, probably a difficult day. Every GR day is a difficult day if it is

within 100 kilometres of a mountain. But

not a long day. Moreover, I’ve had the

benefit of a full day of rest in Briancon.

I’m ready for anything.

And for once I was right.

It was only ten kilometres up the valley of the Durance to its source in

the pass at Montgenevre. Nevertheless, there

was also a total ascent of some 900 metres, if the figures on my Garmin map are

to be believed – a record for me.

So it was a slow and arduous but attractive day. I passed over an amazing single-arched bridge

spanning the gorge at Briancon to the eastern side of the river, then up and up

a rocky trail through a pine forest, with glimpses of the highway on the

western side, wending its way, switchback after switchback, up the gorge.

Other than the silent but eloquent protest of my hamstrings and glutes, a great silence prevailed in the forest. For the first time, however, I encountered several groups of day-hikers coming from the other direction – one group indeed surprised me in a private moment at the side of the trail. But eventually the path led me right into the pass, where the trail and the river and the highway all converged. At this point, the mighty Durance is nothing more than a brook, tumbling happily down the valley, unaware of the great destiny that awaits it below.

And so here I am now in Montgenevre, which, sad to say, has

all the attraction of an abandoned strip-mall. That sounds harsh. But it’s true. No doubt at other times of the year, it’s

different. But not now, in

September. For the village of Montgenevre

is first and last a ski-resort, with a side-hustle in summer outdoor

sports. Every building strung along the

highway is either a hotel, a restaurant, a sports-shop, a trinket store, a spa,

or a ski-rental place. And most of them

are closed. The place is dead.

Fortunately, my little hotel is the liveliest place in town,

like the manager’s office in a funeral parlour when they break out the Scotch

after-hours. My room has a huge double

bed along with two single beds – “so you can invite all your friends,” jokes

the manager. And the hotel has an expansive terrace, where I’m now drinking a Koenig Ludwig Weiss (Blanche) beer, with a

slice of orange floating on top. Don’t

ask me why.

Everyone in the village (all ten

of them) come by the terrace, along with numerous groups of motorcyclists that

roar into the parking lot opposite the hotel.

But now it’s almost 7 pm and I’m just about the only one left in the

place. Time, dear reader, to call it a

day and go off in search of one of the few restaurants that the hotel manager

assures me is still open. If he’s wrong,

there will be hell to pay.

Day 7 - Wednesday, 13

September. Montgenevre to Oulx – 18.6 km

The story goes that a young curate, new to the diocese, was

invited for breakfast by the bishop.

Somewhat nervous, the curate managed to get through the meal without

mishap. At the end, the bishop glanced

at the curate’s half-finished plate and inquired: “How was your egg?” The curate paused, then said brightly: “Parts of it were good.”

That about describes my day.

It started with a light sprinkling of rain as I left Montgenevre and set

off down the road for the Italian border, which I passed at some indefinite

spot before reaching the companion village of Claviere. There I turned off the road and took a track

with a big sign saying “Via Francigena”.

It was the first such sign I’d seen since the early days of the trek in

northern France, while we were still following the standard Francigena trail

and hadn’t succumbed to the allure of Mediterranean shores. It felt good to see it again.

I was looking forward to the Gorges of San Gervasio, about a

half-hour distant, which feature a Tibetan suspension bridge as well as a

spectacular walk though the narrow cleft carved by Piccola Dora river.

But when I finally reached the point where the trail plunged down into the gorge (which was indeed spectacular), I encountered a barrier with a sign saying that the trail was closed for repairs. I briefly wondered whether I shouldn’t go ahead anyway. But then I thought what a nuisance it would be to find the trail washed away and have to climb all the way back up. So after nosing around for a path to regain the road without retracing my steps – there wasn’t one! – I regretfully returned to Claviere and set off down the highway, which I would then follow for the rest of the day, all the way to my destination in the village of Oulx, some 18 km distant.

It was a long, anxious trip, hugging the left side of the

road while the traffic roared past.

Fortunately, there was a verge about a meter wide, demarcated by a white

line. And while the traffic wasn’t very heavy,

it wasn’t exactly light either. Most

drivers swung away to avoid me, but they couldn’t always manage to do that when

there were vehicles coming the other way.

And I quickly learned to press myself against the side whenever a large

truck approached, to avoid being sucked in by the vortex of air. The worst part came at the start, when the

road plunged into a tunnel – about 2 kilometers long – which I had no choice but to

enter. Luckily, the meter-wide verge

continued all the way through, but the noise was deafening.

The other good point was that, although walking by the side

of a busy road isn’t much fun, it also has its advantages. It was downhill all the way, a drop of almost

900 meters, and a hiking trail could have made the trip quite demanding – with

lots of ups and downs on steep stony paths.

On the road, the gradient was perfect for my knees – so that I covered

the long stretch from Cesana to Oulx in no time at all. Now I’m looking forward to some

straightforward countryside hiking, as I gradually leave the mountains and make

my way down the valley of the Piccola Dora to Torino.

The town of Oulx itself is a jumbled, decrepit, unevenly

modernized, busy place – not at all like

some of the touristy, nicely preserved villages encountered along the way. People actually live and work here, and the

place is bubbling with energy and life.

There are motor repair shops cheek by jowl with tiny supermarkets next

to actual clothing shops next to actual sports shops next to actual pharmacies

and cafes.

Big posters emblazoned on the walls describe various types

of Via Ferrata located in the mountains above the town. These are climbing routes of differing levels

of difficulty laid out for people who aren’t really climbers. They feature ropes and cables slung along

pathways that follow tiny ledges across the face of cliffs, as well as iron

rungs fixed into the rock to elevate you to the next level. The idea is that if you follow the prescribed

route with a certain amount of sangfroid and care, while managing to hang on

tight, you will be delivered safely to the end. Not for the faint of heart. Nor for a hiker with dead legs.

As for that hiker, once again I’m sitting in a local bar

drinking beer – Leffe Rossa – while I write this blog. There’s a lot of activity and noise in the

place – with a small dog barking vociferously at the table in the corner, while

his owner repeatedly shouts “Basta!” at him in a shrill, ear-piercing

voice. I’d go over and strangle the

little brute (the owner too) if I didn’t feel so tired. It seems that fatigue is the key to virtue. All the best saints kept themselves very busy.

Day 8 – Thursday, 14 September. Oulx to Exilles – 13.9 km

Never stay in a village that doesn’t have a bar. Restaurants are fine, of course. As Napoleon observed, armies march on their stomachs – and hikers are no different. Food – plentiful food – is a necessity. But as Napoleon must have known, restaurants in France and Italy only open after 7 pm. And what did his armies do when they arrived in a place, tired and dusty, in the late afternoon? Did they lay down their packs and play boules on the village green? No, dear reader, they repaired to the bar.

This revelation came to me during a rest stop along a trail high in the mountains this afternoon, as I prepared myself for the rigours of the long descent into the valley and eventually to my B&B in the tiny village of Exilles.

I was thinking how nice it would be to sit down and have a beer when I arrived. And then I was struck by an awful thought. Did the place even have a bar? I’d taken the trouble to ask my B&B hostess if there was a restaurant. But I never inquired about a bar. Out came my phone, and a frantic search on Google set the world aright again. Yes, there was a café/bar, right in the centre of the village. And, as we shall see, what a place it turned out to be.

The first indication that something odd was afoot came as I approached the village, a jumbled collection of stone houses with slate roofs on the side of a gorge, with a huge ancient fort looming on a bluff beyond. As I crossed the stone bridge over the gorge an old woman coming the other way stopped. She looked me directly in the eyes and, while smiling, asked me who I was and where I was coming from and whether I was walking all the way. I answered as best I could in my shaky Italian, and she continued looking at me as if trying to make up her mind about something. I said farewell and turned to go, and then spotted, just on the other side of the bridge, a remarkable waterfall tumbling down a wall of black rock into the ravine. I expressed surprise, because I was sure it hadn’t been there before. The old woman nodded and, still smiling, said “it’s beautiful isn’t it”, and went on her way.

It was only four o’clock and my B&B wouldn’t open for another hour, so I headed down the narrow cobbled street searching for my promised drink. The place was almost deserted, with only a couple of elderly folks returning my greeting from their doorways as I passed. And there, prominently situated on the tiny main square beside the church, was the bar, a splendid old place dated 1895, with two archways in its façade, one devoted to the bar, the other to an all-purpose grocery store.

I entered the bar to order a coffee and a beer, then went out and took a seat at one of their tables across the way, beside the church. The golden beverage that was delivered to me came in a goblet marked Moretti, but one sip told me differently, dear reader. This was no ordinary beer. It was the elixir of the gods.

I sat there for an hour or more, observing the life of the village, which seemed to proceed at an almost magical pace. When I’d gone inside the bar to give my order, it had been packed with men, all talking at once in loud voices from table to table. But when I glanced inside again, not much later, the men had mysteriously disappeared without me noticing. Meanwhile a cabal of elderly ladies had gathered on a long bench on the other side of the square, where they sat in the fading sunlight and gossiped, throwing covert glances my way. A little girl with long silky hair came by on her bike and circled around, then went to chat with the old ladies. A garish gold-coloured car crept up the street and parked, and the skinny driver disappeared through an ancient archway. A middle-aged couple made several trips up and down the street carrying a strange collection of things in a wheelbarrow. A white and grey cat with a long feathery tail came by to make my acquaintance and play with my hiking poles. A young woman smiled and greeted me like an old friend as she entered the grocery store. It was as if I had been transported back some sixty years, to the Italy I’d encountered in my teens, when we’d made a family trip to Europe.

Then I thought back to my meeting with the old lady on the bridge – who’d acted like a gatekeeper. And it dawned on me. This was no ordinary village, dear reader. It was an enchanted place – an Italian Brigadoon.

Day 9 – Friday, 15 September. Exilles to Susa – 14 km

G.K. Chesterton says somewhere that the rolling English drunkard made the rolling English road. But I’m not sure how anyone, no matter how drunk, could have made the paths I’ve been following this past week.

“But wait,” says a reader. “Aren’t you tracing the route of the Via Domitia, the first Roman road constructed outside Italy? And aren’t the Romans famous for the straightness of their roads?”

It’s good to have such picky readers. They keep you honest. Yes indeed my path does roughly follow the Via Domitia, which was as straight as a road could be when passing through the mountains. The problem is that the actual route of the old Roman road is now fully occupied by the highways and the railway, leaving no room for hikers, save only on the strip at the side of the road, which you follow at risk of interacting so intimately with motorcyclists leaning into a tight turn that you can smell the marijuana on their breath.

So, to be fair to the nameless drudges who designed the path of the Via Francigena, they probably had little choice but to opt for some blatant insanities. Given their mandate to avoid busy roads, and given the nature of the terrain – a tight mountain pass, with the hills on either side riven by deep gorges every kilometre or so – what else could they do but jerk you this way and that – up and down, back and forth, round and around? But it would also seems likely that these drones carried out their mandate with a vengeance, chuckling to themselves as they imagined you drooping with fatigue as you climbed yet another steep stony path, or rounded yet another meaningless curve.

“Enough of this whining!” someone mutters. “Tell us something interesting, upbeat, funny, unusual.”

Hmm. Does it have to be true?

Actually, I have to say that the past two days of walking have been pretty good. Though the routes have been anything but easy or logical, they’ve also been extremely beautiful, sometimes breathtaking. This morning’s route from the magical village of Exilles led me up past the immense fort that squats on a hill like the castle of Jabba the Hutt, a mountainous pile of grey stone with angular walls and wings.

The route continued along the northern side of the valley on paved but virtually empty secondary roads, so high that even with a sturdy barrier at my side I got dizzy just glancing down the 500 metre drop to the foaming waters of the Dora Riparia, at the bottom of the gorge.

Noontime brought me to the village of Chiomonte, where I was seized by the scruff of the neck and dragged into a small restaurant. Struggling valiantly, I was strapped into a seat and forced to eat a dish of pollo al limone on pain of death, while a glass of white wine was poured down my throat by an Italian acolyte of Dick Cheney. I escaped from this culinary dark site an hour or so later, and was led by some fanciful Via Francigena signs through a bewildering maze of woodland paths, no longer caring where I was going or where I ended up.

Surprisingly enough, I did actually make it to the town of Susa, where I must have intended to go, because the people at the hotel desk recognized my name.

So here I am, dear reader, winding down yet again in a sidewalk café, filled with chattering students and families, all eating and drinking and calling out to passersby and jumping up to exchange kisses. The light is fading and the pollo al limone has worn off. I think it’s time for dinner. I promise to eat prudently. I say nothing about the wine.

Day 10 – Saturday, 16

September. Susa to Chiusa San Michele – 30

km

Today was a long, long slog through the rain – all 30

kilometres of it, from the town of Susa to the village of Chiusa di San

Michele, in the shadow of the ancient monastery – the Sacra di San Michele –

perched like an immense dungeon on the crag above. I left town a bit later than usual and

arrived only at 7:30 pm, tired and damp, with the beginnings of a blister on my

left foot. I looked at myself in a road-mirror

along the way and thought “You are a soggy sight indeed”!

The good thing is that the path was almost entirely level

from start to finish. The mountains were

receding on either side, so that the valley was much wider now, with room for

secondary roads and paths on the river plain.

Fields and vineyards were more frequent, and my route was lined with

small villages and farms and residential properties much of the way. My hike had an almost continuous sound track

of barking dogs, and at one point a concert of alpine bells from a herd of cows

in the field at my side.

The rain wasn’t so bad really – more of a slow drenching

drizzle than a downpour. And my Goretex

rain jacket and pants reliably kept out the wet, even if they upped the sweat

factor, so that I was drizzling from within before long. The dogs are a nuisance – they rush at you,

barking ferociously, teeth bared, some even throwing themselves suicidally

against the fence, just to show that they’d rip out your throat and play with

your severed bits and pieces if given half a chance. Fortunately, most of them are safely

contained or secured. And for those that

aren’t, it’s good to have your hiking poles at hand and your best drill-sergeant

voice in good fettle.

The larger population meant that there were cafes in several of the villages, so that I was kept nicely caffeinated and calorized throughout the day. And there was entertaining street art along the way, encouraging weary pilgrims to persist in their journey, because in truth “viatores sumus omnes” – all of us are travellers.

The route was varied, sometimes following paths or gravel

tracks, other times dirt roads or paved secondary routes with little

traffic. There was a longish trek along

a highway at the end, but that was my own choice. It was getting so late that I feared the more

meandering hiking route wouldn’t get me to my B&B until 8:30 pm, when I’d

be walking in the dark. I was late

enough as it was – having texted my hosts several times, each time extending my

expected time of arrival. They’d already

gone out for the evening by the time I arrived, well after the check-in

deadline, and I had to struggle to open an enigmatic key-box, as tricky as a

Rubik’s cube, in order to enter the combination I’d been given.

But once I was inside, the world was restored to order. The B&B was not simply a room but a large

suite, with a spacious living room, ample bathroom and shower, and a bedroom as

big as a barracks, not to mention the balcony overlooking the main street of

the village.

Outside my window now (as I write the following morning) they are setting up stalls for a market the length of the street. And my host, a young red-haired giant named Alessio, has carried my breakfast on a tray down from their apartment upstairs, with a hot cup of cappuccino, croissant, brioche, sweet bun and fruit. There are bottles of juice available in the frig and a coffee machine on the sideboard, so any thought of a healthy breakfast has been banished from my mind. Carbo-loading is what it’s all about – the technique that powers track stars over the finish line in record time. I’ll be happy if it helps me limp out of the village with a modicum of dignity.

DAYS 11-12 - Sunday-Monday, 17-18 September: Chiusa San Michele to Rosta – 25 km; Rosta to Torino – 17.5 km

As it turned out, Day 11 was another very long day. It wasn’t meant to be that way. But it was all my fault. I can’t blame the gnomes that designed the hiking

route, much as I would like to. It all

started while I was having my evening meal in Charlie’s Place, the only

restaurant open near my lodgings in Chiusa di San Michele, where I’d dragged

myself after the 30 km marathon the day before.

As I worked my way through a quarto of red wine, my mind turned to the

question whether I could possibly scale the crag tomorrow where the Sacra di

San Michele is located.

And my answer was definitely not. It would mean a climb of what looked like 500

metres, and then (more seriously for my knees) a climb all the way down the

other side of the mountain, before continuing to my next destination in the

village of Rosta.

Yet, as the evening progressed, and I was served with an

immense platter of affettati misti, followed by a delicious agnolotti with meat

sauce, I came up with a plan, which seemed entirely sensible at the time. Maybe I could persuade my B&B hosts to let

me leave my pack at their place while I made a fleet-footed ascent up the path

to the Sacra, a quick visit, then a skip down the path again to reclaim my pack

before resuming my journey. A brilliant

plan, I thought. It would be a terrible

shame not to visit the Sacra, reputed to be one of the leading architectural

sites in Europe. And, unencumbered by my

heavy pack, I could make short work of the ascent and descent and set off for

Rosta in a flash.

And that, dear reader, is what I did. But when I made this brilliant plan it was

dark at night. And I hadn’t had the

chance to take a good hard look at the hill.

I imagined that the pathway up would be a lazy looping trail, dappled

with sunlight, trod by the feet of a thousand pilgrims into a soft powdery

soil. And indeed, by any rational

measure, the path should have been exactly that. But it wasn’t. It was a trail so steep, so difficult, so

strewn with boulders of every size and shape, that many a pilgrim must have

toppled to the wayside, to be interred where they fell. My only question, as I toiled up the hill,

was whether I would be the next victim.

And if I managed to make it to the top, how in God’s name would I get

down again? For I had foolishly left my

hiking poles at my B&B, thinking they wouldn’t be needed. And I could imagine myself tumbling headlong

during the descent, as I tripped over a rock or slipped on the rubbly surface.

Nevertheless, when all is said and done, the trip was well

worth it – even if next time I will take a taxi. For the Sacra must be one of the most

extraordinary edifices of its kind. Built

on the top of a rocky precipice, the massive building rises through several

levels linked by steep staircases, from the monastery at the bottom to the

soaring church on top. The crag where

the Sacra rests has been incorporated into the construction, so that even near the

building’s highest point one encounters spears of rugged rock in a staircase or

massive granite shoulders bulging through a wall, as if nature could not be

kept at bay.

And the church that crowns the site is an oasis of tranquillity, where even the droves of chattering tourists are reduced to awed silence. It perches on top of the monastery like a gigantic piece of flotsam – a medieval Noah's Arc come to rest on the peak of Mount Ararat.

A pamphlet tells me that the Sacra di San Michele is one of a series of religious sites devoted to the Archangel Michael, running from the Skellig Michael in Ireland through St. Michael’s Mount in Cornwall, to Mont St. Michel in Bretagne, then to the Sacra itself, onward to Monte Sant’Angelo in Puglia, and finally to the Monastero di San Michele in Greece. All these sites are strung along a perfectly straight line, says the pamphlet, which features a map illustrating the point, even showing how the line can be extended to end in Jerusalem. I wonder if this can possibly be true, dear reader, given the diversity of the sites and dates of construction. But the map looks convincing. Ireland doesn’t seem to have been towed out of its normal location, nor has Italy been tilted at an odd angle, so I’m willing to suspend my disbelief.

I was so bewitched by the Sacra that I spent much more time

there than I’d anticipated, and my slow tortuous descent down the

killer-of-pilgrims path didn’t help much either. So it was already mid-afternoon by the time I

regained my B&B in the valley, grabbed my pack, and set off for Rosta, some

15 km distant. Fortunately the route was

fairly flat and meandered through several interesting sites along the way,

affording me parting views of the Sacra.

These entertaining speculations were somewhat deflated not

long afterward, as I followed the grassy track skirting the village and came

across an historical plaque indicating that an early Nobel dynamite factory was

located in the ruined building at the side of the trail. Another mystery solved! But still, dear reader, I stand by what I’ve

said. An annual Nobel prize for the best

bar in the world would not only right a grievous wrong but more importantly

improve bar service throughout the globe.

It was well after dark when I dragged myself up the long

hill to my B&B in the village of Rosta, arriving at 8:15 pm. Note to self: remember to check the elevation

of accommodation. But my host, Giorgio,

was welcoming and my rooms were comfortable and there was a lively restaurant

not 100 metres down the way. So all was

well in the world.

But I was tired the following day. Very tired.

And my hiking route took me some 17 km through the outskirts of Turin

into the centre of the city along the highly urban and unattractive Corso

Francia. Of this, the less said the

better. Fortunately, the blister that

had been developing on my left foot had been caught in time, and the

miracle-working Microspore tape seemed to be keeping it at bay. It started to rain about an hour before I

reached my Airbnb, so I was dripping from every point of extremity (my nose

being the most prominent) when I finally arrived at my destination.

But tomorrow is a rest day!

And the next couple of days after that are relatively short. So my feet, my legs, my hips, my back, my

shoulders, and most importantly my head will have time to get back into good

working order – or as good as they are ever likely to be.

Days 13-14 – Wednesday-Thursday,

19-20 September: Torino to Gassino Torinese – 18 km

During my free day in Turin, did I take the time to tour the

famed Egyptian museum, or view the exhibition devoted to the Holy Shroud (the

Shroud itself is safely tucked away in a church somewhere), or visit the astonishing

cathedral, or stroll about the many fine squares and shady avenues? I did not, dear reader. I did absolutely nothing. Even the word “did” in the previous sentence

suggests a level of activity far higher than the actual state of affairs.

“What then did you … er … not do?” asks a sympathetic

reader.

I sat in my Airbnb flat resting my legs as the washing

machine whirred and rumbled in the corner.

I caught up with my emails and blog.

When my stomach told me it was time, I ventured outside for 100 metres

to eat at the same local restaurant two nights in a row. When I was thirsty in the afternoon, I

repaired to the bar at the next corner, where as it turned out, a group of

rowdy students had gathered to celebrate a friend successfully passing his

doctoral exam. He arrived a bit late,

still dressed in his formal blue suit, but crowned with a laurel wreath. A red satin banner was draped across his

chest like the victor in a beauty contest with words announcing that he was now

“Dott. Ric.” – the equivalent of a Ph.D.

The entire group broke into repeated choruses of “Dottore! Dottore!”, while he grinned and passed around

the wreath for people to try on.

Now a word about my flat.

I have to say that, although it was well-situated in the downtown core,

and decorated in the almost-latest Milano style, with a view of a handsome

street below, the place was genuinely creepy.

For one thing, despite many communications back and forth about my

precise time of arrival, the owners, “Angela & Roberto”, did not give me a

clue about how to get into the flat until well after I’d arrived. I waited in the rain for some time outside

the iron gates of the massive old apartment building, before repairing in

despair to a local coffee shop. Then

finally came the instructions. “Press

number 13 on the list outside, turn right and come up to the first floor, where

we will greet you.”

At last! I did what I

was told and watched while the huge gates made a sort of groan, then after five

seconds swung ever so slowly open, like the gates to the underworld. Inside, I discovered that the building was

actually hollow, with an immense courtyard.

I turned right, was buzzed through yet another door, and went up the

stairs. A young man was standing by the

door to flat #1 (not #13 as I’d expected).

He looked at me curiously as I passed.

“Roberto?” I asked. He gave me an

embarrassed smile to indicate that he was not in fact Roberto, nor was he Angela. He was just someone they’d sent along to do

the honours.

He gave me a quick tour of the flat, then a set of three

keys, one for the outer gates to Hades, one for the inner doorway to the realms

above, and one to the flat itself, then made his departure. It was only later that I discovered that the

key to the gates of the underworld worked just fine, and the key to the flat

did too. But the second key, the crucial

key that admitted me to the upper echelons, did not work at all. Or so I concluded, as I stood outside the

door somewhat later attempting to get back in, trying the key every which

way.

I stood there panting, wondering what to do. Maybe I’d have to bed down in the vast

courtyard. At least I’d be out of the

rain. Oh dear God! Had it come to this?

Perhaps the key was just finicky. Let me try again.

And try again I did.

And again. And again.

It was then that I discovered that the key worked if you

happened to have the fingertips of a safe-cracker. You just have to move it very slowly back and

forth, listening for tell-tale clicks and sensing minute vibrations. Then you

turn it ever so gently and – wonder of wonders – the door opens.

Not long afterward, I received another email from “Angela

& Roberto”, instructing me to watch a YouTube video that explained the many

features of the flat. Once again I did

as I was told, dear reader, and watched as a man purporting to be “Roberto”

walked vaguely about the flat, gesturing at this and that, and offering

basically the same shreds of information as the young man had done before.

Do “Angela & Roberto” actually exist? I have my doubts, dear reader. “Roberto” was a trifle too slick, in my

opinion, to be the actual owner of an actual flat. He was like one of those guys you see on TV pretending

to be a doctor or a dentist, trying to sell you something. I guess I don’t really care whether Roberto exists. I just wish he’d told me about

the key.

All right, that was my day in Turin. Today was another thing entirely. If my arrival in the city along the acne-pitted corridor of the Corso Francia was depressing, my departure this morning along the elegant Via Mazzini could not have been more uplifting. I loped along, spirits high, having escaped from my bizarre flat at 7.30 am. The avenue brought me to the left bank of the River Po – a river I’ll meet again in my travels. And this, dear reader, is a river! Not so impressive as the Amazon or the St. Lawrence or the Nile, perhaps, but even in its infancy majestic. My route led along an elevated terrace by the side of the Po, then across a bridge, and down a well-signed bike and hiking path, which was furnished with some whimsical benches for weary pilgrims.

I passed through lush countryside with views of the broadening river, all the way to the village of Gassino Torinese, where I discovered a roadside restaurant filled with local workers. I grabbed a lunch on the terrace out front, while a dizzying array of cars and trucks and motorcycles roared by at breakneck speeds, as if auditioning for Mad Max. Then I climbed a long steep winding road into the hills above the village to reach my accommodation in an agriturismo, a working farm that offers accommodation and meals.

And welcomed I was, with open arms by the smiling hostess,

who sat me down in the courtyard and brought me chilled sparkling water, a

double expresso, and a whole plate of miniature cookies, which I ate with

unceremonious abandon.

I’m now in my room overlooking the courtyard and the valley beyond, writing this blog as I await dinner. The storm that my weather app had been promising all day long has materialized, and hopefully will rain itself out overnight so that I can set off in sunshine again tomorrow. In the meantime, dear reader, glancing from my balcony, I can see lights agleam in the dining room across the yard, and thoughts of sugarplums dance in my head.

Day 15 – Thursday, 21 September: Gassino Torinese to Chivasso – 15 km

How do these things happen?

After I’d arrived at my family-style hotel in the town of Chivasso and

been ushered to my room, the proprietor came knocking on my door to tell me

that my reservation was actually for tomorrow, not today.

“Non c’è problema!” he said, waving his hands, which I

suppose was true because I seemed to be the only guest in the hotel (though more

arrived later). But it gave me a good

scare. Had I actually skipped a day in

my carefully planned itinerary, throwing off the entire schedule? This would not be the first time, dear

reader, that I’ve royally screwed things up.

I rushed to check my booking.

The man was right. My

reservation was for Friday. And today

was definitely Thursday. Oh rats! Did that mean all my subsequent bookings were

off a day? I could feel the sweat

prickling on my back as I contemplated what a fine mess that would be. I hastily reviewed my reservations for the

ensuing days and …

The sun broke through the clouds. Everything else was fine. And I realized what had happened. The next few days of hiking cross an area

where I’d had enormous difficulty finding any accommodation at all – a sort of

black hole in the Italian landscape – so much so that many pilgrims throw up

their hands and take the train. As a

result I’d changed my itinerary several times as I struggled to find a way of hiking

across this no-man’s land. Eventually

the problem was solved when I sent an email to a restaurant located in the

middle of the desert and they agreed to put me up in one of the rooms they kept

upstairs. But in the course of all this

pother, I’d somehow forgotten to update the booking for Chivasso. So I’m not a total idiot after all. A bit off-kilter, I grant you.

Today was a relatively short day. I’d left my agriturismo overlooking the Po valley just before 9 am, with the mist draping the hills and a firm prediction of rain sometime in the afternoon.

Once I reached the floor of the valley, it was smooth going, as flat as a fritella all the way. And the route was also well-marked, which was a blessing given the confusing web of farm roads that criss-cross the fertile valley. Interestingly, many of the Via Francigena markers point two ways – south-eastward to Rome, my own destination, but also westward to the shrine of Santiago di Compostela in Spain, at the terminus of the famed Camino.

The markers gave me the sense of being part of a larger

enterprise – a very ancient one – as untold numbers of pilgrims have moved back

and forth between these two destinations for more than a thousand years. And as I walked along the muddy trail

skirting the fields close to the Po River, I wondered how many other misguided

folk had done as I was doing, placing their feet in exactly the same spot to

avoid the same pothole in the track.

Do not think, dear reader, that I am without reflective

qualities, that I am completely unaware of the idiocy of what I’m doing. I think back to the first time I encountered

markers for the Via Francigena while on short hikes in Tuscany with Mary Ann, some

fifteen or twenty years ago. Eventually

I looked the name up and learned that it was a long trail leading from the pass

at Montgenevre to St. Peter’s Basilica in Rome – then later discovered that in

fact the trail started at an even more distant remove, in Canterbury, England –

the destination for the pilgrims in Chaucer’s tale.

I remember thinking what a crazy, wild, wonderful thing it

would be to walk the entire trail, from start to finish. I never really thought I’d do it. It was just an insane idea, a pipedream. But gradually the notion took root. Others had done it. They’d even written guidebooks describing the

path in detail – its many glories and pitfalls.

And my son, Mike, seemed interested.

That settled the deal. So in May

of 2015 we set off together from Canterbury, having received the blessing given

to pilgrims at a candle-lit altar in the dark crypt of the Cathedral. We then wandered in a circle in the suburbs

of Canterbury for an hour or two, having missed a marker pointing the way to

Dover. A presage of things to come.

When Covid forced the cancellation of the hike in 2020, and then

again in 2021 and 2022, I wondered if I’d ever complete the pilgrimage. I knew that this section of the route was

probably the most difficult of the entire trip – climbing through the pass at

Montgenevre and then plodding for endless days across the Po valley. But if I was ever to reach Rome, it had to be

done.

So here I am, with the tough climbing all behind me and the

dreaded traverse of the Po valley still ahead.

It’s a long day tomorrow – 30 km to the restaurant/hotel in the middle

of nowhere. And it’s another long day

after that, at least 26 km to the town of Vercelli, where the western and

northern routes of the Via Francigena converge.

When I awoke from my nap in the hotel at Chivasso with my legs still

aching, I wondered briefly whether the train wouldn’t be a good idea after

all. And then I pictured myself sitting

in the railway car dumbly watching the rice fields of the Po valley speed by. And I decided no. Not as long as I could still hobble

along. And I’m nowhere near the hobbling

stage, even if I no longer have the naively confident stride of the early

days. A glass of Barbera wine in the

café where I’m writing this blog has only reinforced my resolve. Wine has that way with me.

Do any of these meandering reflections answer the question

why I’m doing this thing? It doesn’t for

me, dear reader. Perhaps it does for

you.

Day 16 - Friday, 22

September. Chivasso to Tenuta Colombara (26 km)

During the previous stage of the hike, my buddy Kent and I encountered

two French pilgrims while we were hiking along the Via Domitia toward the

Alps. Both men were coming from the other direction – from their home

town of Briancon – and both were heading for Santiago di Compostela in Spain,

although they seemed unaware of one another. Interestingly, both of them had

also hiked along the Via Francigena from Briancon to Rome, and they offered

very different accounts of their travels through the Po valley. The first

one – whom we dubbed the Grumpy Pilgrim – said it was a dreadful place: totally

flat and hot, nothing but rice fields day after day, ridden with mosquitoes,

little of historical interest, little of any interest whatsoever. Hell on

earth, in short. The second fellow – inevitably dubbed the Happy Pilgrim

– had a very different take on the place. He said it was a lovely,

tranquil pastoral setting, and best of all totally flat.

I’m only one day into my traverse of the Po valley – which will last basically all the way to Pavia and beyond – so it may be premature to offer an opinion. But based upon my journey today, it looks like I’m going to be in the camp of the Happy Pilgrim. The hike from Chivasso to Tenuta Colombara, while some 30 km long, was delightful from start to finish. Yes, the land is flat. Yes, there are fields as far as the eye can see – first mainly corn and now arboreal rice. Yes, there’s relatively little of historical interest. Yes, there’s a certain monotony to the hike, since the landscape changes only slowly and than only in slight gradations. But even in late September, the area is bursting with life. The fields are still mainly green and there are tractors and all sorts of improbable agricultural devices rattling along the roads and coursing through the fields. There is a wonderful freshness to the landscape, with lots of interesting things to notice – the elegant lines of poplars between the fields, the plethora of canals and streams and irrigation channels that crisscross the entire area and often run alongside the road, the succession of small well-kept agricultural centres and villages, with at least one bar or restaurant where you can rest your legs and quench your thirst with something cool.

And after struggling up and down many a steep path all the

way through the mountains, I can’t say that my legs are objecting to a bit of

flat. The kilometers seem to melt away beneath your feet as you stride

along – and yes, you really can “get into your stride” on these long straight

roads, without all the twists and turns of previous days of hiking. It

feels good as you swing along without a care in the world, the sky wide open

all about you, a line of blue hills to the south, and steeples and towers visible

in the distance. In fact I was able to see my destination, a rambling old

inn in the middle of the rice fields, almost an hour before I actually reached

it. So I virtually galloped the final

six kilometers from the farming village of Lamporo along a track beside a

gushing agricultural canal.

This final sprint, I should add, was a mistake. I did

it because I’d promised the landlady to get there by 5 pm and I was an hour or

so late. In the end, of course, it didn’t matter at all. Yet the

gallop took a toll on my poor legs, which ached and complained so much after

I’d gone to bed that I finally got up and took a Tylenol – the first of the

trip – which allowed me get to sleep.

And, wonder of wonders, my legs actually feel pretty good

this morning – enough to get me through another long hike to my next

destination, the town of Vercelli, where I’ll have a rest day and the chance to

do some laundry. Badly needed laundry. I sweat so much when I’m

hiking that I try to avoid eating in the interior of restaurants, convinced

that I’m stinking the entire place up. Even if I start with fresh clothes

in the morning, within an hour or so I’m dripping with perspiration, my shirt

clinging to my body, my pants glued to my thighs. And I can’t always

start the day with fresh clothes. In fact, this is my third day of

wearing the same stuff, so my imminent arrival must announce itself to villages

many hundreds of metres before I actually get there.

Days 17-18 – Saturday-Sunday, 23-24 September: Tenuta Columbara to Vercelli

(30 km)

The hike to Vercelli turned into a 30 km marathon, to match the 30 km I covered yesterday. It rained a good part of the way, as I kept pace with the fringes of a storm-front that was moving slowly eastward at roughly my own speed. Just behind me I could see blue skies and fluffy white clouds, but immediately overhead it was grey, with sheets of rain hanging from the dark clouds ahead. To the north, the foothills of the Alps brooded darkly in an unbroken chain, like an army poised to invade the plains below. It was only when I reached the village of Lignana, about two hours before Vercelli, that the skies overhead cleared and the sun burst through.

“You’ve brought the sun with you,” smiled the barman in the

village, where I stopped for a coffee and a sparkling water. When he

heard that I was hiking along the Via Francigena he wanted to charge me only

one euro for the lot. I thanked him but demurred, insisting on paying

full price. But when I checked

my change later, I found he'd given me a hefty discount.

Vercelli turned out to be a lively and interesting town,

with crowds of students and people of all ages thronging the pedestrianized

centre of the place, which boasted a multitude of cafes and restaurants.

And the locals are friendly.

Almost immediately after I arrived in town, a man stopped his car to ask

if I was a pilgrim. I was indeed, I replied in my best Italian. Ah,

he said, and proceeded to direct me to the nearest pilgrim hostel. I

didn’t need to go there, of course, because I’d already made reservations at my

B&B. But I appreciated the interest and the gesture.

As I may have mentioned earlier, Vercelli is the place where the branch of the Via Francigena coming from the north converges with the western branch from Montgenevre. From here on, I’ll be following the classic route, all the way across the Apennines into Tuscany – but that’s for next year, with the following year taking me through Umbria and onward to Rome.

Day 19 – Monday 25 September:

Vercelli to Palestro (11.3 km)

“Anything to eat?” I asked, casting an eye about the

bar.

The young barmaid shook her head.

“How about for dinner?” I persisted, thinking of the sign

outside that advertised a prix fixe from Monday to Friday.

Another shake of the head. “The kitchen is closed

today. It’s Monday.”

This wasn’t what the sign said, but I wasn’t going to argue

the point.

The bar was a sleekly modern establishment, all glass and

polished steel, located by the highway outside the village of Palestro, where I

was staying for the night. The bar was

my best hope for finding somewhere to eat this evening.

A man standing near the cash, pitched in.

“What about the Bar Centrale in the village?” he asked the

barmaid.

She shrugged.

The man turned and called to someone playing the gambling

machines in the corner. I couldn’t hear his response, but it must have

been discouraging, because the first man raised his eyebrows and turned back to

tell me that everything was closed.

This was going to be a problem. It seemed as if my

options for tonight were either starvation or fasting. There’s a subtle difference between the two, dear reader. Starvation is thrust upon you,

fasting you own. But either way you don’t eat anything.

This called for a beer – a nice cold Grimbergen served in a

goblet with a gold rim to match the colour of the beverage within. I sat

down on the terrace outside and took a few sips, thinking that if I just waited

long enough, something was bound to turn up.

No sooner had the thought passed through my mind than the

barmaid came hurrying out and asked whether I could do with some bread and

sausage.

Could I do with bread and sausage? Si, si, si!

And a white-haired bloke I hadn’t seen before served up a

basket of fresh bread and an enormous chunk of savoury bologna. I pushed

back my laptop and devoured most of what was laid before me, as if it were my last meal – which indeed it could well be, at least until tomorrow.

I had spent most of the day trudging from Vercelli along

elevated farm roads through an expanse of rice paddies, with the snow-capped

mountains of the Alps hovering in the sky to the north.

Along the way, I came across a post that, in addition to the

standard Via Francigena marker, featured one proclaiming “The Jerusalem

Way”. And that started me thinking. I’d already contemplated

continuing my trek southward once I reached Rome. The official route of

the “Via Francigena nel Sud” has been demarcated and a guidebook issued. The path runs south of Rome for over nine

hundred kilometers, passing through a series of ancient ports along the east

coast – Bari, Brindisi, Otranto – before reaching the heel of the Italian boot

at Santa Maria di Leuca. But somehow I’d never seriously thought of going

all the way to Jerusalem. Of course, that’s where pilgrims of medieval

times would be heading. None of this fancy hiking for the sake of

hiking for those practical folks. Jerusalem or bust!

Well it would be wonderful indeed to walk the entire way

from Canterbury to Jerusalem – with a few minor stretches of water in between

of course. And Jerusalem is … well, what can you say about

Jerusalem? The name itself conjures up all sorts of wonderful

images. When people ask me where I’m headed, I answer Rome, which evokes

at best a polite interest. What they really want to know is whether I’m

going the other way – westward to Santiago di Compostela. That’s the

place where virtually everyone I meet dreams of hiking, somehow, someday.

But were I to say, I’m headed for Jerusalem – now that might push me a few

notches up the prestige scale!

In mid-afternoon I reached the ancient village of Palestro, located

in a clearing at the end of a forest track and dominated by a medieval brick

tower that I recognized as my B&B for the night.

Although today’s hike wasn't long, and yesterday was a rest day, I felt a kind of weariness in my bones that testified to the cumulative impact of weeks of hiking. I was glad to be there, and glad for the warm welcome from my youthful hostess, who ushered me up a steep external staircase to my bedroom in the tower, which dates back to the year 999, the lone survivor of once extensive fortifications.

I unpacked and showered, then set off to find something to

eat, for I was ferociously hungry. As I

walked through the deserted streets of the village in a blaze of sunlight, I was

swept by a strange sensation. Perhaps it

was the effect of fatigue, or hunger, or the flawless blue sky. But as I gazed about me, I felt as if I’d passed

into another dimension, such was the depth of the silence, the slumber, the sense

of time suspended. The brilliance with

which the houses and roofs and balconies were delineated seemed unnatural, or

rather super-natural – elevated to a clarity beyond the realm of ordinary

experience. Nothing moved. Not a leaf, not a particle of dust. No door opened or closed, no stray cat

appeared from an alleyway or slunk into the shadows. No voices drifted from a courtyard. All was profoundly still.

The sense of timelessness was only sharpened when I came

across a sports-field at the edge of town, where some teenage boys were playing

football with all the raucous intensity of a World Cup final – the eternal struggle

of shirts versus no-shirts. It was as if

I’d stepped across an invisible frontier back into the realm of time. I stopped to watch the boys for a while, struck

by their raw passion and energy, their uninhibited love of the game. And it occurred to me that if heaven really

exists, it must have room for this boisterous sports-field and not just the supernaturally

silent streets on the other side of the temporal divide.

The story of my search for food has a happy ending. That evening, on heading back into the village, I discovered that the Bar Centrale was indeed open. As I sat at a rickety table outside the bar watching the light fade, they served me some very tasty tosti with cheese and ham, topped by another beer and some chocolate gelato for desert. I guess heaven has tosti as well.

Days 20-21 – Tuesday-Wednesday,

26-27 September: Palestro to Mortara – 21.9 km; Mortara to Gropello Cairoli – 27.9

km

The hiking has become a bit tougher recently, because the

blister on my left foot that I thought had been nipped in the bud reared its

ugly head once again during the rainy day on the way to Vercelli, when my socks

got wet, causing abrasion. Every morning

I bind up my feet with Microspore tape until I look like I’m being mummified

from the soles upward. This stratagem usually

solves the problem until the afternoon, when my feet become increasingly sore

and sensitive, registering every small pebble and bump in the road as if I’m a mobile theodolite.

One thing that has come home to me is that hiking for 30 km

in a single day is courting trouble, even when the land is perfectly flat. And doing it for several days in quick

succession is a death wish. “Never

again!” I say bravely. “Nothing over 20

km!” But sometimes the scarcity of

accommodation doesn’t leave you much choice.

And the flatness of the terrain, as my sister Patsy tells me, does not

shield you from wear and tear. In fact,

the opposite seems true. When you’re walking or

climbing on uneven ground you’re placing stresses at differing angles on

continually shifting parts of the body, so that the impact is diffused. By contrast, when every step forward is

exactly like the step before, as is the case when you’re striding along a

straight road, the same joints and muscles are being stressed over and over

again.

Yet it has to be said that the hiking has been beautiful all

the way through the Po valley, with the dew on the rice paddies sparkling in

the morning sunshine, and great warehouses for storing the precious arboreal

rice punctuating the landscape like agricultural versions of the palace at

Versailles.

So, asks a reader, has the valley of the Po river turned out to be as dreadful as the Grumpy Pilgrim made out? Not at all. It’s actually quite a lovely pastoral setting, with neat fields separated by elevated farm roads and occasional shady paths along agricultural canals or rows of windbreaks.

The area features many varieties of storks and cranes (including the ibis), which dot the fields like clerics in cassocks of white and black. This time of the year the plain is also populated by armies of agricultural machines of wondrous size and complexity. You realize how massive these things are when you confront one on a narrow farm road with deep ditches on either side. The monstrous wheels roll past your toes as you squeeze onto the miniscule shoulder, trying to avoid toppling into a muddy stream of water.

No, dear reader, I did not topple into a muddy stream. Near-misses don’t count.

Day 22 - Thursday, 28

September. Gropello Cairoli to Pavia –

18 km

The past couple of days have involved long hikes and late

arrivals, giving me just enough time to shower and set out in search of refreshment. But this afternoon I finally reached Pavia –